So Amazon recently threw its hat into the thunderdome of online digital music sales. The store’s big brand name and huge retail operation instantly make it one of the top tier marts for digital music. As Amazon MP3 is seen primarily as a challenger to the iTunes Store’s throne, I originally wanted to do a compare and contrast with that gorilla, but later thought that unfair to eMusic, who consistently claims to be the second largest online store on the net. The iTunes Store has more than enough going for it that an equilibrium will eventually be met with whatever competition comes its way. eMusic, however, might be quite vulnerable to Amazon’s might and muscle.

throne, I originally wanted to do a compare and contrast with that gorilla, but later thought that unfair to eMusic, who consistently claims to be the second largest online store on the net. The iTunes Store has more than enough going for it that an equilibrium will eventually be met with whatever competition comes its way. eMusic, however, might be quite vulnerable to Amazon’s might and muscle.

But just how does that muscle shape up?

I took a look at Amazon MP3, trying to gauge its place on the market and judge its strengths and weaknesses compared to its more established rivals. Each service was evaluated using the following criteria:

- Format & Quality

- Selection

- Search & Ease of Use

- Pricing

- Artwork and Tagging

- Free Stuff

Format & Quality

Amazon MP3

As the store’s name suggests, Amazon MP3 provides music in the MP3 format. MP3 is incompatible with any type of rights management and the most notable claim of AMZMP3 is the freedom of the file format it is willing to sell. MP3s, of course, work on virtually all portable devices. Amazon MP3’s also pitches its files as being high quality. The site claims to supply a very healthy bitate of 256kbps for its downloads, but the files I’ve purchased have averaged 214 (VBR) kbps. Though they sound fine to my ears, it is less than the site advertises.

Getting info on the file tells me that it was encoded using LAME 3.97.

eMusic

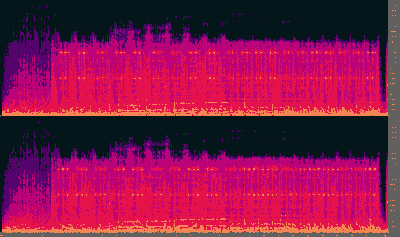

Like Amazon, eMusic provides free and open MP3 files and has been doing so since 2003. The MP3s are encoded around 192kbps (VBR) using LAME 3.92. The music sounds great.

The iTunes Store

The iTunes Store has been the spearhead in the adoption of the AAC format, selling AAC encoded files since the store’s 2003 inception. AAC is billed as a successor to MP3 and is particularly noted for sounding better at lower bitrates. At the time of this writing, the iTunes Store is providing two flavors of AAC. The standard encoding is 128kbps, which to its credit sounds pretty good. The store benefits from having the songs encoded from the original master recordings, rather than being ripped from a CD. Throughout much of the store’s history, however, Apple has been forced by its contracts with record labels to include the much-criticized and oft-despised rights management, FairPlay, on all song downloads. Most of the songs it sell come packaged this way.

Recently though, the store has made moves to free its music from those restrictions. The iTunes Plus service sells songs with no DRM attached and doubles the bitrate to 256kbps. There’s a lot of debate about the merits of AAC vs MP3 at higher bitrates, so the benefit of the increase may not be that significant, but surely, it can’t hurt. Currently, about 1/3 of the store’s inventory is offered via iTunes Plus.

Winner: 3-way tie (with edge to Amazon and eMusic). The files supplied by each store, while not lossless, sound quite adequate for the majority of listening applications and music systems. iTunes loses a couple points for the continued existence of FairPlay, but the way things are trending, it probably won’t be around for much longer.

Update 28 March 2009: Apple has announced that by April 2009, 100% of its music content will be DRM-free. It that comes to pass, then there really will be little to debate about format choice. All three stores will be using files that are compatible with a large number and wide range of players and hardware.

Selection

Each store likes to boast about its large catalogue. iTunes is by far the largest with about six million songs to choose from. eMusic and Amazon both claim to offer more than two million songs each (Playlistmag says eMusic has 2.7 million UPDATE 11/7: Macworld reports that eMusic now stores 3 million songs in its catalogue, while Amazon’s complete list shows 2,479,112 at the time of this writing). Impressive numbers all around, but catalogue size doesn’t mean squat if it doesn’t have the songs you’re looking for. So, I went through the music libraries of three people and randomly choose 20 songs from each. I then looked for those songs on all three services, giving one point for songs on the album I was searching for or half a point for the song in another context (soundtrack, compilation, greatest hits, etc).

Here are the results:

The iTunes Store is easily the champion in this contest, besting its two rivals combined. Of the 60 songs searched, iTunes scored 46 points, Amazon finished with 20 and eMusic ranked in with 14.5. Within those results, there were only 2 instances where either AMZMP3 or eMusic had a song that iTunes did not and 5 instances where eMusic provided a song that Amazon did not. In total, there were 10 songs that none of the stores carried in their inventory.

But besides the run-of-the-mill catalogue, each store has its selectional perks.

iTunes offers tons of exclusive content, such as its iTunes Originals series, celebrity playlists or the AOL Sessions series.

eMusic has an extensive selection of “eMusic Only” releases, many of them full live concerts. The site also hosts the world’s largest collection of DRM-free music, which eMusic notes come from 20,000+ independent labels. However, the iTunes Store and Amazon are both gaining in that respect. What you won’t find, however, is any of the majors, which is a bit ironic considering that Universal used to own the place.

In contrast to eMusic and iTunes, Amazon MP3 is lacking in the exclusives department. There’s no “Amazon Presents…” or the like, just search-and-download. In a notable coup, however, AMZMP3 is the first and only store to offer digital downloads of Radiohead’s albums (plus one single for the completeists out there). Though the band’s label, EMI, also participates in Apple’s iTunes Plus program, Radiohead only wants to sell complete albums, which violate Apple’s policy to offer track-only purchases. Thus, OK Computer at Amazon, but not at iTunes. Update 3 June 2008: Radiohead’s complete catalog is now also available DRM-free from iTunes.

Winner: Each store offers a reason to shop there, but at the end of the day, it’s the iTunes Store that will most likely be selling what you’re looking to buy.

Search & Ease of Use

iTunes

In typical Apple fashion, the iTunes Store screams ease of use.

The storefront is built into the iTunes desktop app, making for one stop shopping. Apple has gone to great lengths to integrate the offline library management functions of the program with the online sales environment. The ubiquitous “iTunes Store” arrows and the “Minibrowser” might be a little intrusive, but those can be turned off.

Once in the store, finding songs/albums/artists is trivial; just type it into the search bar, though most of the time you have to sort through movies/tv shows/podcasts/etc in the results. The store does a pretty good job of segregating the various types of media. iTunes falters when it comes to the exploratory level. In the four years since its launch, I’ve never found it all that comfortable or appealing to browse the place for an extended period of time.

Like almost all online shoppes, the iTunes Store allows users to leave feedback, ratings and comments about albums. It also provides rudimentary recommendations in the form of “People who bought X also bought Y.” Users can also contribute to the store via iMixes, compilations put together by individuals and submitted to the store. However, the presentation is pretty sparse and there’s minimal “social aspects” to them, i.e. you can see what another person has rated or look at their iMixes, but you can’t “befriend” them or interact or see recommendations based on tastes you might have in common.

Once purchased, songs download straight into your library. It’s seamless. But be sure to make a backup of everything you buy. Apple only allows you to download the song one time, though if a catastrophic event wipes out your collection, the store does permit an unpublicized one-time re-download of your purchase history.

Some songs, usually determined by length, are not available as a single download, but must be purchased as part of an album. That can be a drag when you just want the one song.

eMusic

eMusic’s storefront is HTML-based. The store can be accessed and songs downloaded from any web browser. Recently though, the company released eMusic Remote as a way to integrate the online store with the desktop. The app runs on Mac/Win/Lin and is based on the Mozilla browser. Think: iTunes-Store-inside-Firefox. eMusic Remote provides an easy way to navigate the store and manage downloads, which can automatically be added to your iTunes library, should you so desire.

The site’s search feature could use some vast improvements. Often, the results it returns are far too many, especially for simple queries, and they don’t seem to be prioritized and are not sub-sortable. Sometimes, I find it easier to do a Google site search instead: site:emusic.com.

Previewing music comes in the form of downloadable m4u playlist files, which can be opened by iTunes or Quicktime Player. The process can be tedious for single tracks, but is really quite nice for checking out complete albums. Though, I’d rather they switched to Flash-based, in-browser previewing. UPDATE 04/17/08: Hooray! eMusic recently switched to an in-browser sample preview system. It greatly improves the ability to get a taste for a song/band/album before deciding to buy.

In contrast to iTunes, eMusic’s social aspects are more robust. While similar in theory to what iTunes does, the execution is better. Each album’s page shows any reviews that members have written; that’s not special. But, where iTunes says “People who bought X also bought Y,” eMusic is more specific, giving recommendations based on what a handful of particular fans also enjoy. These make great springboards for further exploration.

Also, an album’s page shows which users’ ‘playlists’ it appears on. Akin to iMixes, a user playlist can be whatever the author wants it to be. A playlist can be as simple as someone’s public bookmarks, or as indepth and voluminous as “80+ Reasons Why Japan Rules,” much like Amazon’s Listmania.

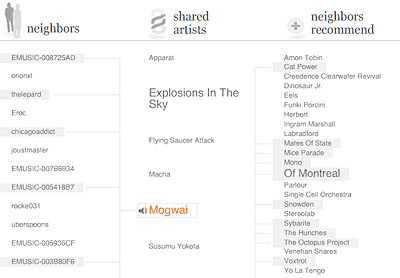

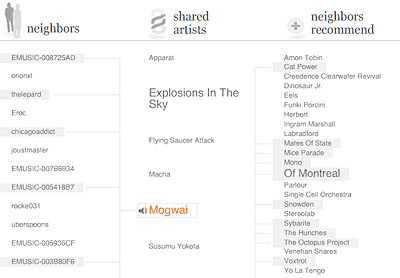

One of the best music discovery tools I’ve run across on any platform is eMusic’s Neighbors screen. It shows fellow music fans with similar tastes. Hover over a shared artist and get recommendations based on that artist. On my current screen, based on my interest in Mogwai, I have five neighbors telling me to check out Cat Power, Of Montreal, and eight other artists. Using this tool, I’ve found a number of new and interesting bands based on my intersections with my musical neighbors.

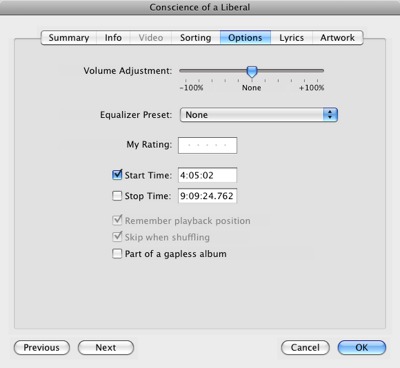

eMusic, unlike iTunes, offers no restrictions on the number of times you can download a purchase. Hard drive melt? Just log into your history a grab it again. Also, unlike iTunes, eMusic has no restriction on songs based on length. There are no “album only” purchases. Every song, even a 30 minute opus, is available as a single purchase.

eMusic Neighbors screen

Amazon MP3

AMZMP3, like eMusic, is browser-based with both direct download for singles and a desktop app for grabbing albums. The company knows how to run a web store, and its expertise shows. If results are available, a search will return a list of artists, albums and song that match. Songs can be previewed immediately via a nifty on-page Flash-based system, or more details on the album can found on the album’s page, which integrates the feedback, reviews and ratings from the physical CD’s entry in the vast AMZ database.

Likewise, if MP3s are available, the option to buy them appear on the actual physical CD’s page. A useful gimmick that doesn’t seem to be in place though is, “Buy a CD, download MP3 immediately” type bundles. I suspect that would result in a fair amount of up-selling.

Getting the actual music files is straightforward enough. For single songs, click the “Buy MP3” button, confirm payment and a single MP3 will be all yours for the downloadin’. Whole albums require the Amazon MP3 Downloader program. When purchasing an album, a reference file is downloaded to the desktop. That reference file tells the Downloader which album to retrieve. Then the music begins to flow. When finished, the app will auto add to iTunes if requested. The process requires a couple extra steps, but it works.

Like iTunes, some music at AMZMP3 is album only, though it’s hard to know what or why. Those Radiohead albums for example, no individual songs can be purchased. The length of the song isn’t necessarily a factor. There are some 17 and 18 minute-long Mogwai tracks available separately, while at least one 11 minute Sonic Youth song is album only. Adding to the confusion is the store’s somewhat perplexing price structure.

Overall though, the site is still considered to be “public beta,” so we can guess that it will improve with time.

Winner: Each services is pretty much on par with the others on the ease-of-use front. None have a particularly show-stopping difficulty. iTunes gets points for the all-in-one solution, while Amazon is a known quantity that now extends to MP3 sales. eMusic’s search can be challenging, but its re-download policy and music discovery tools make it very appealing to the adventurous.

Pricing

The iTunes Store charges a flat $0.99 per song for individual tracks. Albums cost the sum of all songs, or $9.99, whichever is lower. It’s the same way throughout the store; there are no variations.

Unlike iTunes, Amazon charges a variable price for downloads. At launch, Amazon’s typical price per song is $0.89, though some are $0.99. Most complete albums run $4.95 to $9.99, though I’ve not figured out how those prices are computed. Sonic Youth’s A Thousand Leaves is 11 songs at $0.99 each or $7.97 for the whole album, a difference of $2.92. Pink Floyd’s The Wall is currently $8.99 for all 26 songs ($0.35 vs $0.99 a piece), whereas Dark Side of the Moon has some songs for $0.89, others for $0.99, or $7.99 for the album, a difference of only $0.62. It doesn’t make much sense, but in some cases, you might find a better deal than the iTunes Store.

eMusic’s business model is different than the pay-per-track services of Amazon and iTunes. Similar to the Netflix model, subscribers pay for a membership plan to access a certain number of downloads per 30-day cycle, rather than paying for songs individually. In my case, I pay $14.95 for 50 downloads every thirty days. If I download all 50 songs, I end up spending just $0.30 per song. There are more extensive bulk plans that will bring the price down to $0.25 per song. Also, the length of the song doesn’t matter; a 30 minute epic track costs just one download credit, as does a 30 second interlude.

Maximizing the value of one’s subscription requires diligence however. It’s never happened to me personally, but if one forgets or is too busy to retrieve their current downloads, well then, they get squat for their $15. In my case, the worst I’ve ever done is have 6 credits left at the end of the cycle. I’m usually plagued by the *other* subscription conundrum: Wanting a 10-song album, with only four credits until the next refresh. Most of the time, I solve this dilemma by grabbing the first four songs, bookmarking the album in my “save for later” area, then return first thing after the refresh (I have an iCal reminder tell me when it’s time). Alternately, I find eMusic to be an inexpensive way of exploring classical music.

Winner: On price alone, eMusic wins, provided you take full advantage of your subscription. With the $14.95 plan, you’ll be on par with iTunes as long as you download at least 15 songs per cycle. At this time, Amazon is also undercutting iTunes on price. This could change after the honeymoon period, as more popular songs might be priced higher than $0.99, but for now, iTunes is the loser on the money factor.

Artwork and Tagging

Songs from all three stores come with comprehensive ID3 tags, providing song name, artists, album, genre, etc. AMZMP3 provides high-quality album art embedded in the file, while iTunes supplies it in a separate sidecar file. eMusic will download a jpeg along with the MP3s, but it must be manually added to the files. eMusic’s jpeg however is a pitifully small 150 x 150 pixels. so I either use iTunes to retrieve the album cover or search for better art using sloth radio. UPDATE: 4 Dec 2008: However, a recent redesign of the site does provide high-quality album art in the browser. It must still be manually added to the music files, but at least it’s right there when you download an album.

Winner: Slight edge to Amazon for embedding the art, slight knock to eMusic for making me work to find better art.

Free Stuff

The iTunes Store provides free content across its entire product line, from TV episodes to movie clips to sample audiobook chapters and of course, music, not a day goes by without some kind of freebie posted and available for consumption. Most notable is the Single of the Week, which changes every Tuesday. There are entire websites devoted to tracking the latest zero cost offerings at the store.

Likewise, eMusic also offers free downloads. You don’t even need to be a customer to snag them. eMusic offers two types of freebies. One, the Daily Download is updated every day. Other, long term free tracks are kept in their own part of the site. At the time of this writing, there are roughly 70 tracks up for the taking. Since eMusic caters to those outside the mainstream, most of the free tracks are from the relatively obscure, so if you’re looking to explore a bit, here’s a chance to do so without spending a cent.

I’ve not found much zero cost music at AMZMP3. There’s certainly no breakout section saying “Free Downloads Here.” However, the list of every available MP3, sorted by price , reveals a total of 36 songs available free of charge. The store is young, so who knows what kind of free stuff is planned for it.

, reveals a total of 36 songs available free of charge. The store is young, so who knows what kind of free stuff is planned for it.

Winner: Each store has something to give away, but eMusic gains an edge by not even requiring an account to download it. iTunes has a lot of variety, plus the entire podcast directory and iTunes U, so mucho bonus points there. Amazon lags at a distant third.

::

In terms of service, the stores are fairly evenly matched. Some foibles here and there, but, hey, nobody’s perfect. Amazon is a worthy contender and an appealling place to look when you just have to have a song right now. eMusic pretty much rules for those who enjoy exploring off the beaten path. But if you want to be absolutely sure to find the songs you’re looking for, iTunes can’t be beat. You just might have to pay a premium for the convenience and hope it’s not poisoned with DRM.

Personally, I find each to be a fine service and I see no reason to exclude any of them from my music-buying arsenal. In fact, I look forward to using Amazon a little more. And maybe, just maybe, the pressure will drive those other two companies to improve their digital music services.

Note: In the interest of disclosure, you should be aware that tunequest acts as an affiliate for two of the stores mentioned in this article. They send me a pittance whenever I send them a customer. However, that relationship in no way changes my opinion of each company. The fact is that I would not have chosen to become affiliated were I not already impressed with the services in the first place. They each have their strengths and weaknesses.

Click the New Playlist button. In the window that pops up, we can specify our criteria so that our bookmarkable podcasts appear in this playlist.

Click the New Playlist button. In the window that pops up, we can specify our criteria so that our bookmarkable podcasts appear in this playlist.

, which should be visible if you’ve installed at least one AppleScript, select Quick Convert.

, which should be visible if you’ve installed at least one AppleScript, select Quick Convert.